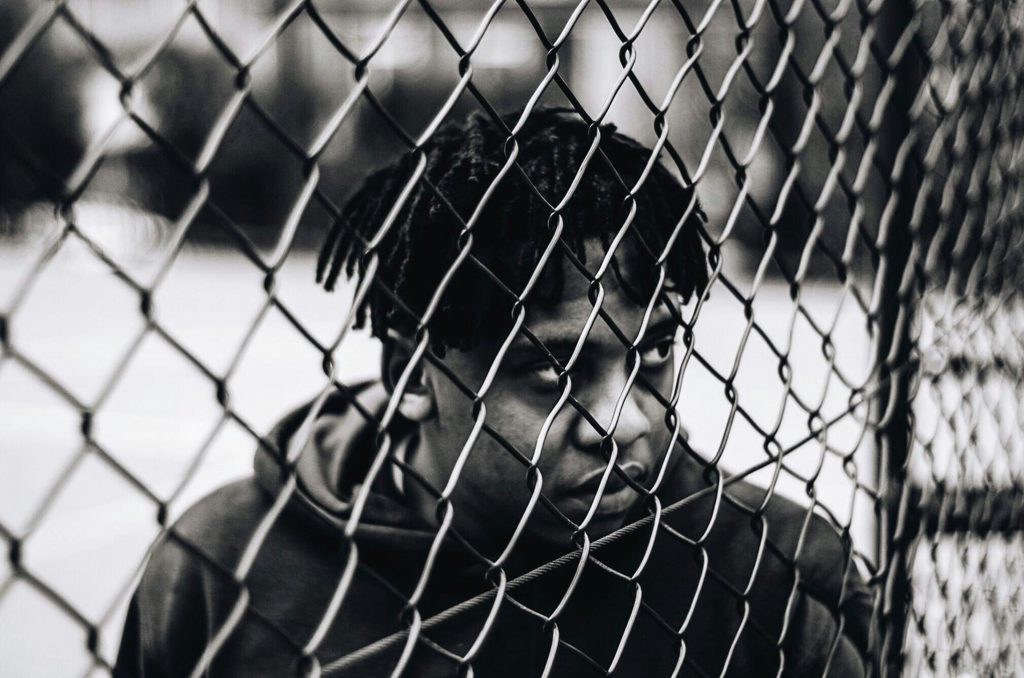

With one of the lowest incarceration rates globally, Norway is recognised as having one of the world’s most progressive and humane approaches to prison with a focus on rehabilitation and reintegration (Berger, 2016). Nevertheless, like most prison populations, there is a high level of mental health and social care need among people in Norwegian prisons. In a nationwide survey, there was evidence of mental disorder in 92% of incarcerated individuals (Cramer, 2014).

The beliefs individuals hold regarding the reasons or causes for their mental health problems affect how they think and respond to them and influence their help-seeking behaviour. ‘Prisonization’ refers to psychological changes that take place as a consequence of prison life (Haney, 2001). Factors that influence these changes include a loss of autonomy and being separated from support networks. The environment and regime of prison can also have a negative effect on mental health.

In order to be able to meet the mental health needs of incarcerated individuals, it is important to understand how they conceptualise their mental health and how those conceptualisations influence their coping preferences. The topic of this blog is a study by Solakken et al. (2023) who aimed to meet this need.

‘Prisonization’ can change how someone thinks, feels, and behaves. There is limited insight into how this might influence their beliefs about mental health and ways of coping.

Methods

A qualitative design was used, and a relativist ontological stance was adopted, recognising subjective realities and co-construction of knowledge between researchers and participants. Fifteen in-depth interviews were conducted across three male prisons in Northern Norway. Participants were predominantly Norwegian citizens with an average age of 44 years. Their experience of prison varied, but all had experienced mental health problems in prison.

The semi-structured interviews lasted 60 to 90 minutes and aimed to explore mental health, prison culture, and help-seeking. Analysis used elements of Grounded Theory, including line by line coding and developing conceptual categories from the data. A collaborative, reflexive process guided interpretation.

Results

Three themes (with associated subthemes) were identified: perspectives on mental health, beliefs about the impact of imprisonment on mental health and beliefs about management of mental health problems.

Participants described mental health as a multifaceted concept involving balance and well-being, identifying coping strategies such as exercise and social contact. They felt that prison life had altered their perspectives on mental health, highlighting the importance of social connections and meaningful activities. Self-isolation was considered to be an obvious sign of mental health problems and symptoms of depression were most frequently described. Participants emphasised the connection between mental health and social environment, noting the impact of stressors in prison on worsening mental health issues. Mental health problems were felt to be caused by a variety of factors including experience of parental neglect, poverty, violence, and trauma.

Prison was inextricably linked to participants’ definitions of mental health, with a clear connection between the prisonization process and deterioration of mental health. Anxiety related problems were commonly discussed. Many individuals shared stories of peers’ experiences and spoke about prison conditions, the amount of time spent alone, lack of autonomy and meaningful activities as being damaging to mental health.

In terms of preferences for management of mental health problems, peers were seen as crucial for support and there was a preference for psychosocial strategies over medication. Although the efficacy of medication was acknowledged, there were concerns about side effects and dependency. However, ADHD was viewed differently; this was considered as a more acceptable diagnosis in prison and participants were more accepting of medication. ADHD was also discussed by participants as being an explanation for their offending behaviour.

Participants perceived that prison conditions such as time spent alone and lack of autonomy had a marked impact on mental health.

Conclusions

The main finding of the study was that participants’ beliefs about mental health, and how issues are managed, is very much integrated with the experience of prison.

Participants varied in their understanding of mental health but tended to attribute mental health problems to stressors in the prison environment rather than internal causes. Both importation theory (Irwin & Cressey, 1962) and deprivation theory (Sykes, 2007) offer perspectives on how participants’ beliefs about mental health are integrated with their prison experience, and the complex interplay of factors: importation theory highlights the influence of pre-existing characteristics, while deprivation theory emphasises the impact of the prison environment itself. Social support and meaningful activities were highlighted as important factors for well-being and non-medical interventions were preferred when it came to management of mental health problems.

Prisoners beliefs about mental health are strongly integrated with the experience of prison itself.

Strengths and limitations

The adoption of a qualitative approach is a strength of Solakken et al.’s (2023) study. This enabled an in-depth exploration of participants’ perspectives on mental health within the prison context. The study also included a sample of participants with diverse experiences of prison from three different prison establishments.

However, as with all research, there are some limitations worth noting. The authors acknowledge that the self-selecting nature of the sample is a limitation of their work; that the views of those who volunteer to take part may be different to those who do not volunteer. Indeed, the authors do caution that the results only apply to the individuals who took part in the study, and they make no broader claims about the generalisability of the work to prisons in Norway or farther afield. Nonetheless, although some context about the prison system in Norway is provided, it would have been helpful to understand how representative the prisons included were of the wider system. Likewise, the authors, rightly, do not provide a detailed description of participant demographics to ensure that anonymity is preserved, but some comment on whether participants were broadly representative of the prison population would have been useful to better contextualise the results.

There is a detailed description of the analysis process which provides a good level of transparency, but the lack of a positionality statement is a limitation. Although the epistemological stance of the researchers is made explicit, understanding how the researchers’ backgrounds and perspectives influenced analysis would have provided a more nuanced understanding of their interpretation of the data.

The qualitative nature of the study enables an in-depth exploration of mental health in the prison context, though this could have been better contextualised in terms of the Norway prison system.

Implications for practice

Despite some limitations, these findings have implications for the development and implementation of mental health interventions and policies within prison settings. In Norway specifically, the authors highlight that improving services for people in prison forms part of the Norwegian governments’ ten- year mental health plan.

The finding that people in prison perceived their mental health as interconnected to the prison environment emphasises the need for holistic approaches that consider the broader social, environmental, and cultural factors that influence mental well-being, as well as clinical symptoms. The authors suggest it is important that clinicians explore and acknowledge patients’ beliefs regarding their mental health to enable effective communication between the health professional and service user, ensuring treatment is adjusted according to need. In addition, recognising the challenges of the prison setting in relation to patients’ mental health, is needed to enhance engagement with treatment.

In terms of policy, the findings stress the importance of mental health promotion in prison suggesting that providing people in prison opportunities to engage in meaningful activity, work and education is important to promote wellbeing. This is in keeping with the healthy prison test adopted by HM Inspectorate of Prisons in England and Wales; purposeful activity is one of the four criteria judged to determine whether a prison is ‘healthy’. Purposeful activity is defined as people in prison being able, and expected, to engage in activity that is likely to benefit them. Policy makers should consider ways to enhance the opportunities for this in the restrictive environment of prison.

Similarly, social isolation is recognised as a risk factor for poor mental health outcomes (Grav et al., 2012) and this study adds to the evidence base advocating the importance of social connectedness. The study recognises peers as a crucial component of social support to promote well-being in prison. Although prison does provide opportunities to maintain contact with friends and family in the community, this is restricted in several ways. Consequently, the importance of peer relationships as a form of accessible support is increased. Peer relationships in prison are not without challenges and therefore research exploring and evaluating peer interventions, such as The Samaritans Listener scheme, to facilitate social support is needed. Improving health outcomes (and beliefs about positive health outcomes) of people in prison is likely to improve the chances of successful reintegration on release. Further research may be beneficial to understand how beliefs about mental health impact people’s motivation for rehabilitation post-release.

These findings suggest that prisons should adopt a holistic approach in improving mental wellbeing, taking into account the broader social, environmental, and cultural factors that influence mental well-being, as well as clinical symptoms.

Statement of interests

None.

Links

Primary paper

Solbakken, L. E., Bergvik, S., & Wynn, R. (2023). Beliefs about mental health in incarcerated males: a qualitative interview study. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 14, 1242756.

Other references

Berger, R. (2016). Kriminalomsorgen: A Look at the World’s Most Humane Prison System in Norway. Available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2883512

Cramer, V. (2014). The prevalence of mental disorders among convicted inmates in Norwegian prisons. Oslo University Hospital. Available at: Hel_oppdatert_Victoria_Cramer_rapport_engelsk.pdf (sifer.no)

Grav, S., Hellzèn, O., Romild, U. & Stordal, E. (2012). Association between social support and depression in the general population: the HUNT study, a cross-sectional survey. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 21,111-120.

Haney, C. (2001). The psychological impact of incarceration: Implications for post-prison adjustment. University of California. Available at: The Psychological Impact of Incarceration: Implications for Post-Prison Adjustment | ASPE (hhs.gov)

Irwin, J., & Cressey, D. R. (1962). Thieves, convicts and the inmate culture. Soc. Probs., 10, 142.

Sykes, G. M. (2007). The society of captives: A study of a maximum security prison. Princeton University Press.