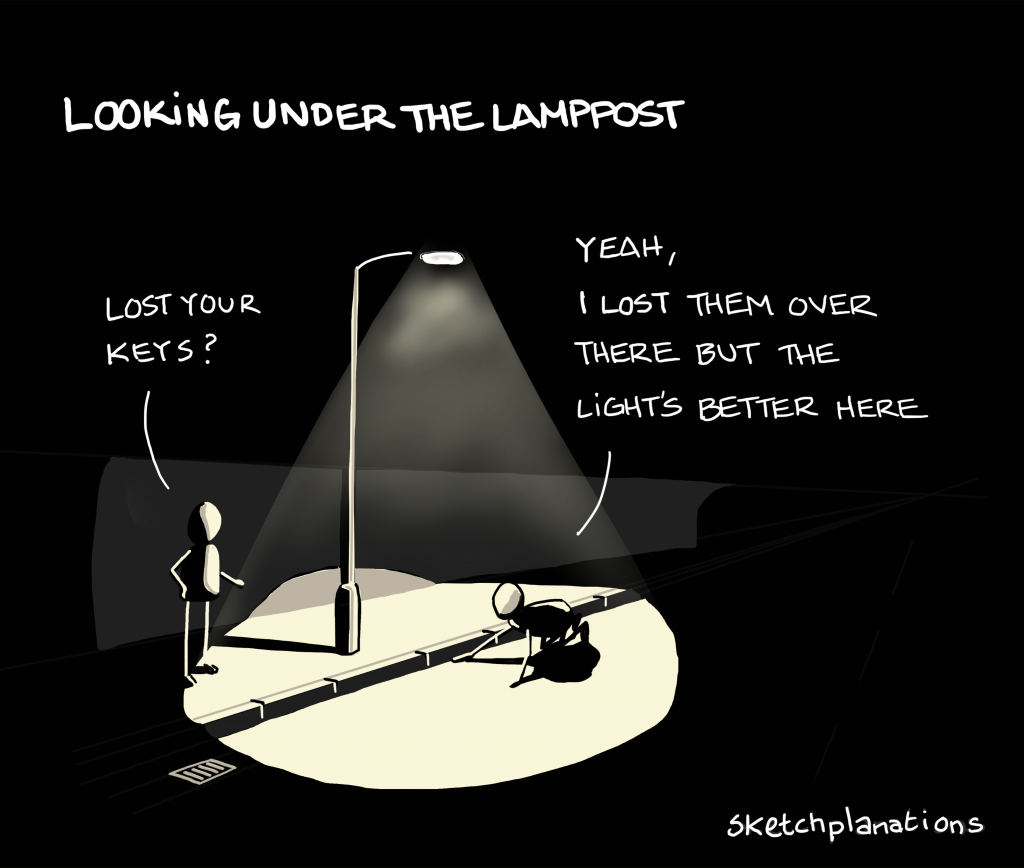

We all know that the social conditions that people live in have a major effect on their mental health. This is well-documented in the academic literature (e.g. Lund et al, 2018; Kirkbride et al, 2024). It is no mystery that living in poverty, dealing with daily threats to your personal safety, or being regularly exposed to racism and discrimination makes people mentally unwell. The big question is what to do about it. An Australian linguist recently analysed news articles on mental health and found that while most articles referenced the social issues that contribute to mental health problems, when it comes to discussing potential solutions they inevitably switch back to individual treatment or self-help, rather than addressing the conditions that are making people ill (Horwood, Augoustinos & Due, 2023).

The authors of this recent umbrella review remind us that social solutions are needed for social problems. They take a systematic approach to identify which actions to address the major social determinants of mental health are supported by the current evidence, which is a useful contribution to policy debates about how to improve population mental health. They also helpfully link these actions to the wider global health and development agenda in the form of the Sustainable Development Goals. Ultimately, however, I think that their review of reviews mostly highlights the limits of the way that we tend to think about “interventions” in mental health research and the need for a broader paradigm, as I will argue below.

We know that the social conditions that people live in have an effect on their mental health. The big question is what to do about it.

Methods

The authors conducted an umbrella review – effectively a review of existing systematic reviews – following established methods. There are of course some shortcomings of this approach (i.e. if nobody has yet done a systematic review of a particular topic then this area of interventions won’t have been included). However, for a question this broad, covering all social determinants of mental health, such an approach is necessary to make the task manageable.

Crucially, they focus on reviews of intervention studies with a control group in order to evaluate the mental health impact of the interventions considered. Although as this was an umbrella review they had to decide whether to include reviews that included controlled and uncontrolled studies, so in practice they included reviews where more than half of the included studies had a control group; it wasn’t clear to me whether they extracted results from only those studies with a control group or not.

There are of course good reasons for this decision. Without a control group it is difficult to conclude whether any change in people’s mental health is attributable to the intervention or if it would have happened anyway. Nor can we tell if there was something else going on alongside the intervention that led to the improvement or worsening of participants’ mental health. The limitation of this approach, however, is that many of the most potentially impactful strategies to address the social determinants of mental health are not easily amenable to controlled trials. National policies to address child poverty, such as reforming the benefits system, for example, might reasonably be expected to have a major impact on the mental health of both children and parents, but there would be no obvious control group. Social determinants of mental health often reflect basic human needs, such as the human rights for food and shelter, and there are obvious ethical dilemmas in withholding such support from people in order to evaluate the mental health impact of having these basic needs met or not.

Thus, the effect of trying to take an evidence-based approach – where the gold standard of evidence is the randomised controlled trial – is to focus attention on strategies that fit easily into the category of “interventions”; in other words, discrete, time-bound, clearly defined services that can be evaluated in the same way that we evaluate medical interventions. These tend to target downstream risk factors that are close to the individual, rather than the bigger structural causes that lead to these risk factors being unevenly distributed across the population, leading to persistent health inequalities.

Results

A total of 101 reviews were included in this umbrella review. Just 23 of these were rated as having high confidence, 14 as moderate, 24 as low and 40 as critically low according to the AMSTAR-2 (Shea et al., 2017). The authors focused only on the findings from the 37 reviews rated a moderate and high confidence.

The included reviews show that some (but not all) interventions targeting intimate partner violence, poverty, employment and working conditions, social inclusion, and bullying, appear to have some mental health benefits. They also indicate a positive impact of some (but not all) psychosocial interventions for people who have lived through humanitarian or environmental disasters. There were some important social determinants – such as child abuse – for which the authors found no evidence of a mental health impact of interventions that target this factor.

Over half of the included reviews in this umbrella review were rated as low or critically low quality.

Conclusions

These findings provide a useful starting point for policymakers looking to improve population mental health to identify interventions for which there is an established evidence base. The results do not say whether the interventions had an effect on the social determinant in question, however, so it’s unclear whether those studies that failed to produce a mental health impact did so because they were ineffective in changing the social conditions that cause mental ill health, or because there is no immediate mental health impact of changing those particular conditions.

This kind of review is unable to unpick questions about where interventions took place, how they were implemented, and for whom they worked, if their effects were variable for different groups. To really understand why some interventions “worked” or “didn’t work”, more theory-driven realist evaluations are needed to unpick the processes through which each intervention operates within its particular context. We need to move beyond asking “what works?” to “what works for whom, under what circumstances, and why?”.

We need to move beyond asking ‘what works’ to ‘what works for whom, under what circumstances, and why?’

Strengths and limitations

The authors acknowledge the limitations of traditional methods for evaluating interventions in the context of complex systems, but don’t entirely spell out the implications for this review. For example, “beyond addressing individual and interpersonal dimensions of child abuse, prevention programs could benefit by addressing systemic contributors, such as cultural or organizational norms, socioeconomic, and structural inequalities”. They state that “a range of study designs are required to develop evidence for social determinants interventions” and recommend the use of novel quantitative and practice-based methods (including natural experiments) and the triangulation of quantitative evidence with qualitative research and implementation science approaches to address questions of mechanisms, context, and culture.

Lots of actions to address social determinants may therefore be promising for mental health, which were not considered by the current review. Many of these are overtly political, for example, regulating industries that exploit people and deplete or pollute our shared resources, clamping down on the fossil fuel companies and industrial animal agriculture that is driving environmental disasters, brokering peace deals, enforcing regulations to prevent industrial disasters, better policing around child abuse and prosecuting sexual offenders etc. The project of creating better mental health overlaps substantially with the project of building a fairer society, and our usual research methods are unequipped to capture the complexity of these societal-level issues.

Are we barking up the wrong tree by focussing on “interventions”? Policies and community-led initiatives often target multiple co-occurring determinants, in iterative, evolving ways. This approach just doesn’t fit with the way we think about “interventions” in research, where a very defined service – which is necessarily narrow and targeted – is implemented and evaluated with a control group. Indeed the authors acknowledge “the tension between standardizing intervention designs and the importance of appropriately tailoring interventions to particular groups and contexts…. Co-produced, interdisciplinary approaches are required to ensure greatest impact”.

The project of creating better mental health overlaps substantially with the project of building a fairer society, and our usual research methods are unequipped to capture the complexity of these societal-level issues.

Implications for practice

This review summarises the current state of evidence on “interventions” targeting social determinants of mental health, but some of the recommendations from the discussion are worth highlighting. The authors write: “There is a need to move away from reactive Western psychosocial approaches, to approaches which aim to prevent environmental events (e.g. climate action) or which address other social determinants (e.g. food security) in the context of disasters”. This, I think, is key. Even some of the interventions included in the current review seem to target mental health in the context of social determinants, falling into the same trap that so many others have fallen into of appearing to talk about changing social conditions, but actually reverting to focussing on individual responses to those conditions.

We need to learn from the research on complex systems and adapt our approaches to evaluation to be fit for purpose when looking at the dynamics of upstream interventions within a system that has many inter-dependent components. And we need to update our understanding of evidence in order to synthesise this kind of information to make policy and advocacy decisions.

This review calls for a shift from treating mental health problems to tackling their root causes, like climate change and food insecurity.

Statement of interests

No interests to declare.

Links

Primary paper

Oswald, T. K., Nguyen, M. T., Mirza, L., Lund, C., Jones, H. G., Crowley, G., … & Das-Munshi, J. (2024). Interventions targeting social determinants of mental disorders and the sustainable development goals: a systematic review of reviews. Psychological Medicine, 1-25.

Other references

Horwood, G., Augoustinos, M., & Due, C. (2023). ‘Mental Wealth’and ‘Mental Fitness’: The discursive construction of mental health in the Australian news media during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 33(3), 677-689.

Kirkbride, J. B., Anglin, D. M., Colman, I., Dykxhoorn, J., Jones, P. B., Patalay, P., … & Griffiths, S. L. (2024). The social determinants of mental health and disorder: evidence, prevention and recommendations. World psychiatry, 23(1), 58.

Lund, C., Brooke-Sumner, C., Baingana, F., Baron, E. C., Breuer, E., Chandra, P., … & Saxena, S. (2018). Social determinants of mental disorders and the Sustainable Development Goals: a systematic review of reviews. The lancet psychiatry, 5(4), 357-369.

Shea, B. J., Reeves, B. C., Wells, G., Thuku, M., Hamel, C., Moran, J., … & Henry, D. A. (2017). AMSTAR 2: a critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. bmj, 358.